Music

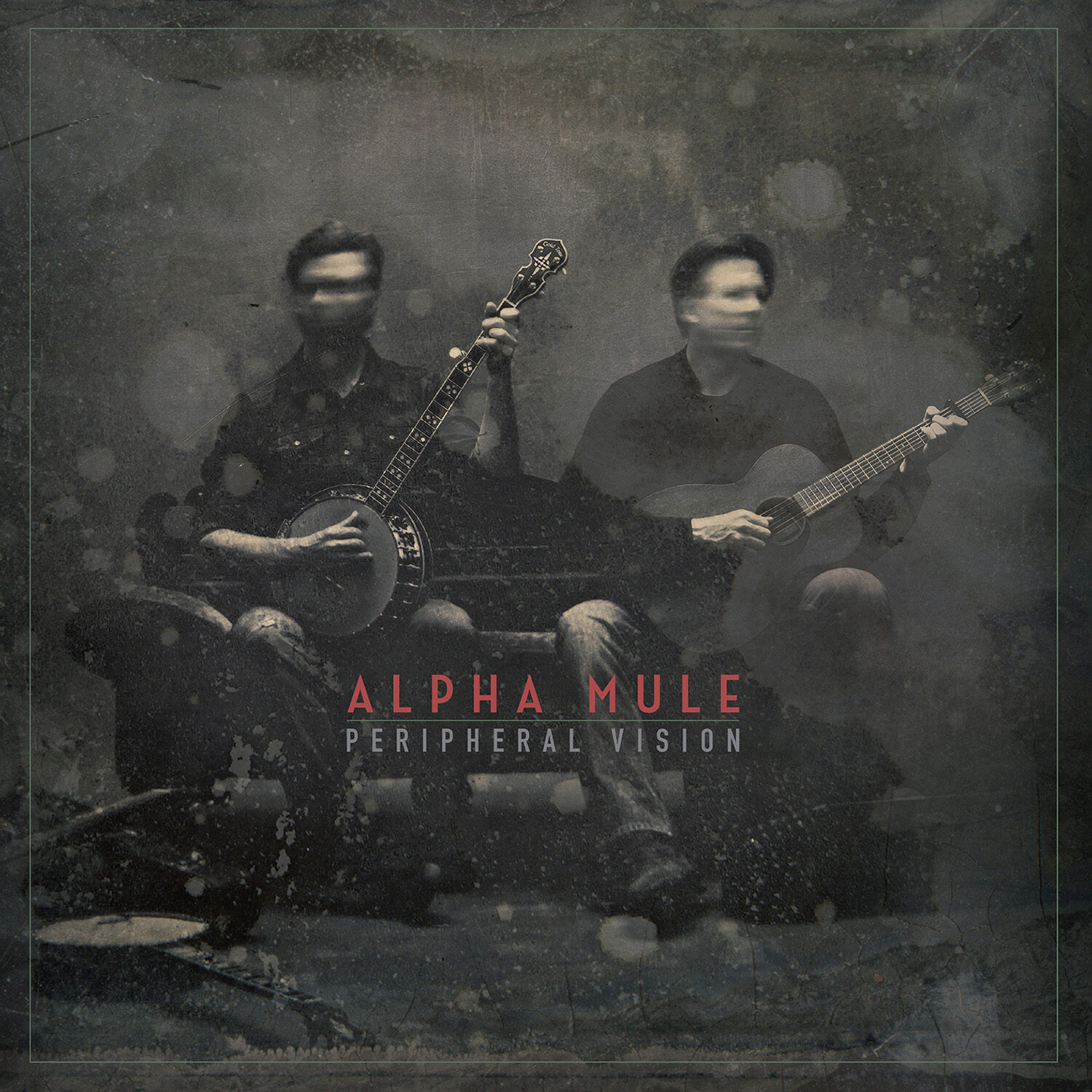

- October 31, 20191 LikeWaveLab StudioOkay, while clearly not about painting, this is a project I’ve been working on for...

- October 31, 20191 LikeJacob ValenzuelaOkay, while clearly not about painting, this is a project I’ve been working on for...